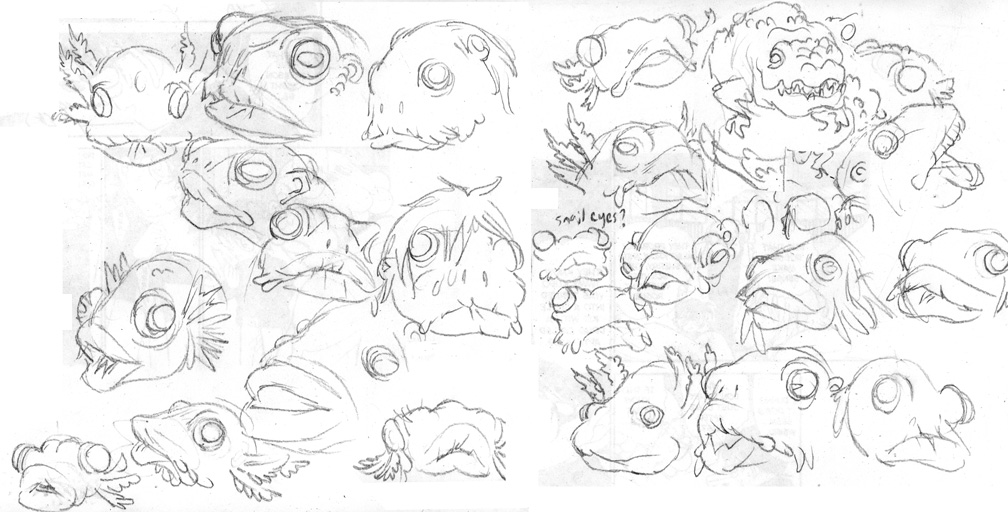

Sarnath Sketches

A few sketches from the upcoming “The Doom that Came to Sarnath” adaptation. (There’s also a few Ibites scattered around the Dream-Quest GN.) More soon!

A few sketches from the upcoming “The Doom that Came to Sarnath” adaptation. (There’s also a few Ibites scattered around the Dream-Quest GN.) More soon!

“When a man rides a long time through wild regions he feels the desire for a city.”

—Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

H.P. Lovecraft’s stories are filled with descriptions of cities, both fictional and real. From the Nameless City of the Arabian desert built by lizard men, to the marginally more realistic Arkham and Dunwich, to his longest single work, A Description of the Town of Quebec, he loved towns and felt — like everyone at some level — that they had an innate existence as more than a cluster of buildings in space. One of his hobbies was antiquarian architecture, examining a town from its streetlamps, its cobblestones, its roofs (gambrel or non-gambrel), its number of fanlights. Cities were his home and hearth, and a way of pinning down the past: a form more visible and intentional than fossils in a riverbed, or the gradual accumulation of topsoil that allows the land to grow grass and trees. As Ken Hite points out in his excellent book “Tour De Lovecraft,” as much as Lovecraft hated urban decay, he was a city boy. The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath is Randolph Carter’s love letter to his ideal city, filtered through the many other not-quite-ideal cities he encounters on his way (“He swore that Ulthar would be very likely place to dwell in always, were not the memory of a greater sunset city ever goading one on toward unknown perils”). In the same way, Lovecraft wrote a thousand love letters to Providence, from his adolescent poetry to the words I AM PROVIDENCE, from a late letter, now inscribed on his tombstone erected by fans after his death.

Like footprints in the sand of nature, cities stick in the human mind. Julian Jaynes, in his book The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, defines civilization by cities: a civilized person, he says, is someone who lives in a city (or community) too big to personally know everyone else who lives there. Pausanias’ Description of Greece, possibly the first surviving tourist guide, describes cities and shrines but rarely bothers to note natural features; in that age before ecological consciousness the pastoral, with its risk of wolves, weather and highwaymen, was not yet a reason to travel (or maybe in that preindustrial time, there was just so much of it, no one cared?). The earliest travelogues were just lists of cities, names one after the other, like the exotic cities that pass along the river in Lord Dunsany’s “Idle Days on the Yann.” At one time, all roads led to Rome; later, in Medieval maps the city of Jerusalem was usually drawn at the center of the world, with the continents radiating out from it.

Made-up cities followed real cities; Alberto Manguel and Gianni Guadalupi’s A Dictionary of Imaginary Places is full of descriptions of them and their romance, their utopias and dystopias, heavens and hells. Places have souls, as Lovecraft expressed subtly in his best stories, like “Dream-Quest,” and bluntly in his worst, like “The Street.” And people have places where they belong. Even Batman has Gotham City and Superman has Metropolis, which, while they make you wonder where there’s room for the real New York City in the DC Universe, give it a special appeal beyond the idea that Spider-Man might be living on your block.

It was important to Lovecraft not only to describe cities, but to create them. Lovecraft admired the fantasies of Lord Dunsany — they were the #1 inspiration for his dreamlands stories– but one of the many differences between their work is that Dunsany never tried to create a consistent mythology, except in his early standalone “The Gods of Pegana”. Except for a rare few linked stories (sequels like “Idle Days on the Yann”, “The Avenger of Perdondaris” and “The Shop on Go-By Street”, “Bethmoora” and “The Hashish Man”, “The Distressing Tale of Thangobrind the Jeweler” and “The Bird of the Difficult Eye,” etc.) Dunsany never reused place-names or created a consistent world that could be mapped (or at least not without making most of it up yourself). Most likely, imaginary names came easier to Dunsany, and he just didn’t feel the need to repeat himself. On the other hand, Lovecraft reused everything, like a bird building its nest. As early as “The Quest of Iranon” he’s making references to “The Doom That Came to Sarnath” and “The Green Meadow.” Abdul Alhazred, his childhood Arabian Nights persona, is still appearing as the author of the Necronomicon 40 years later. Lovecraft didn’t have the thoroughness of Tolkien, but he had the same urge to create a single fictional universe that includes everything he wrote — a Grand Unifying Theory, call it the Cthulhu Mythos or Yog-Sothothery or whatever. Dunsany’s cities and creations are like bits of delicate crystal; Lovecraft’s are like stones rounded by frequent handling.

Lovecraft was a homebody — except for his brief stay in New York, all his life he clung to his childhood city, his childhood furniture (what a shame that there are no photographs of it, his ratty old furniture he loved so much he told Helen Sully he’d go insane if he had to part with it!), his childhood home (or as near a simulacrum as possible, since the original house had been sold). But he was also a traveler, spending days on buses and trains, seeing the world as much as his finances allowed (as a California boy, I have to say, it sucks that he never managed to visit Clark Ashton Smith in California), absorbing new sights and memories. Writing about them. And returning home. Home was the axis of the world around which he spun, his reference point that gave his travels meaning and context.

Dream-Quest is the story of a pilgrimage (one of his rejected titles was “A Pilgrim in Dreamland”), a journey to exotic ports from which the hero returns with newfound appreciation of home. It’s inherent in Dream-Quest that Carter and Kuranes are outsiders, tourists, travelers just passing through but not really meant to settle in these fabulous lands. (As Kuranes sadly discovers.) We see the dreamlands through the eyes of foreign adventurers, not so much through the eyes of Atal the Little Farm Boy from Ulthar. J. Vernon Shea (also quoted by Ken Hite) says that he thinks one of Lovecraft’s inspirations was 19th century Orientalist travel literature such as the works of Richard F. Burton and Charles Doughty. Late 20th century academics would criticize this narrative of the privileged (white) outsider visiting the East to cherry-pick Enlightenment from the local traditions and return home to write condescending portraits of the natives, but on a scale of racism in Lovecraft’s works, it’s downright sweet of him to write a story in which both the heroes AND villains wear turbans. Marco Polo and Herodotus also returned home after long voyages to write about the Mysterious East, after all, and so did Manjiro, long before imperialism and Elizabeth Gilbert. Every traveler thinks they’re someone special, every traveler is a pilgrim and a hero in their own minds. In Orientalism, Edward Said repeatedly criticizes Western tourist-adventurers in the Middle East for never wanting to settle down and actually participate in the lives of the people (to marry a local, for instance), for always keeping their distance; but like Lovecraft returning to Providence (not to spawn, but to die), these travelers could never sever their ties to Home, to their original mindset and place.

The description of Places Far Away is an exercise for the dreamer as much as for the surveyor, as Italo Calvino proved with his amazing book Invisible Cities, a pastiche of ancient travel literature whose frame story is Marco Polo describing the lands of Asia to Kublai Khan, but whose cities are all allegories, exploring different aspects of the meaning of City, how they are designed, how they are lived in, how they are described. The cities in Dream-Quest and Lovecraft’s other dream-stories are not as aerily conceptual as Calvino’s; even the lands the White Ship passes feel like fantasy RPG settings first (Thalarion is described as a “demon city”! So it must be full of demons!! DEMONS!!!!) and allegories second. Lovecraft, like Calvino or Dunsany, builds his world of cities word by word, but Lovecraft’s vocabulary is almost entirely visual and material. He describes the material that cities are built of; their contents, temples, gardens and houses (sometimes ad infinitum); their color; the experience of walking through the parks and up the hills. He occasionally lapses into E.R. Eddison‘s tedious habit of describing the fabulous jewels and gems that cover everything, as if writing them down added to his book’s value.

To be blunt, although he enjoys having them in the background, Carter/Lovecraft cares little about the people who built and inhabit these seashell-like cities. (Or who don’t inhabit them; it’s unclear whether the Sunset City is inhabited, and Lovecraft’s ideal of a beautiful East Asian-style landscape, the haunting Gardens of Yin described in Celephais and Fungi from Yuggoth, is a place where there are no people, “but only birds and bees and butterflies.”) Occasionally we hear about the picturesque onxy-miners and sheep-traders, but Carter doesn’t interact with them much beyond asking directions (nearly every single conversation in Dream-Quest) or finding a room at the inn. There’s certainly no aspect of the sexual tourism so often associated with travel, whether Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Martian princesses, or the shivery anticipation (“adventurous expectancy”?) that new places means new people to sleep with, which is such a big part of Samuel Delany’s city-novel Dhalgren and Schuiten and Peeters’ fanservicey Cities of the Fantastic graphic novels and Italo Calvino’s descriptions of innkeepers’ daughters and beautiful odalisques. Carter/Lovecraft has no time for that nonsense (although Lovecraft apparently liked Burroughs when he was younger, and he just felt embarrassed about it when he grew up); he’s in search of a purer beauty. Dream-Quest is a travelogue written by a shy, or simply introverted tourist; Carter interacts more with monsters and cats (a cat to pet in every port) than with people.

Lovecraft’s dreamworld is one of sights and occasionally sounds, but he rarely describes touches or smells, except in a negative context in the dark and gloomy spots. He’s so unconcerned with physical pleasures that he doesn’t even describe the taste of the food; in “The Doom That Came to Sarnath,” written in his earlier, more decadent phase, Lovecraft goes all-out describing an exotic feast of delicacies, but in “Dream-Quest” Carter hardly eats so much as a bite. Perhaps Lovecraft (who by all accounts had an unadventurous palate on top of not having any money) had, by this time, grown tired of trying foreign food in New York City and resigned himself to a future of eating canned chili and cheese and crackers. Jack Vance and Clark Ashton Smith, those sensualists whose stories of traveling rogues were so much more picaresque than Lovecraft’s “picaresque novel” Dream-Quest ever was, would weep at the missed opportunity.

Given Lovecraft and Dunsany’s love of strange-sounding names (those pins on the map), it’s interesting that the Sunset City in Dream-Quest, the goal of all Randolph Carter’s dreams, has no name. Perhaps this is because it’s Boston and thus to name it would be to spoil the secret, or perhaps, as the Perfect City around which the world revolves, it needs no name. Personally, I’ve suspected that its true name is “Hesperia” (from the Greek word for ‘evening’). There’s no actual evidence for this, but “Hesperia” is the title of stanza XIII of Lovecraft’s Fungi from Yuggoth, which describes a tantalizingly unvisited city beautiful in the light of “winter sunsets,” and it was also the name of a zine Lovecraft once planned to make. Fungi from Yuggoth has other reworkings of imagery which originally appeared in the unpublished Dream-Quest, such as Azathoth, Nyarlathotep and the Plateau of Leng, so perhaps Hesperia is another holdover.

In any case, its name is its meaning: the Sunset City. Why sunsets? Peter Cannon wrote a whole essay about it, Sunset Terrace Imagery in Lovecraft, which I haven’t read. Colin Wilson, in his book A Criminal History of Mankind (the kind of sociological-psychological pop stuff he wrote when he wasn’t writing stories about the Lloigor), proposed that the emotional reaction to seeing a beautiful place from a high vista is derived from primitive hunter-gatherers’ pleasure at seeing new pastures where tasty grazing animals might roam. “We think we feel it in the heart, but it may be in the stomach,” Wilson writes. Is the pleasure in seeing the world, in seeing the landscape from high vistas, simply a kind of biophilia? Lovecraft’s most lovely, most human cities always contain some natural element: Kadath is an icy palace, Teloth is a bleak modern city of gray stone blocks, but the sunset city has its gardens and “grassy cobbles.” Lovecraft’s English-garden vision (or Chinese-garden vision) of an orderly nature, or at least pleasantly arrested decay, is very different from Lord Dunsany’s proto-environmental hate of cities and his love of fields and forests for their own sake. (Tolkien, too, had more love of nature; when I think of Middle-Earth I think of the whole place, of rolling fields and mountains, not of its admittedly nicely described cities.) But then, Dunsany was a rich man with an estate, and Lovecraft, like most people, only had his native streets to wander through.

Perhaps it’s also natural that sunsets make people think of the past, of the remains of the day, of what could have been. It’s probably pointless to overanalyze this: I’m reminded of a Peanuts strip where Charlie Brown tells Psychiatrist Lucy that he prefers sunsets to sunrises and Lucy throws up her hands in exasperation: “What a disappointment! People who prefer sunsets are dreamers! They always give up! They always look back instead of forward! I just might have known you weren’t a sunrise person! Sunrisers are go-getters! They have ambition and drive! Give me a person who likes a sunrise every time!” When I lived in San Francisco I used to love the late afternoons, the way the light carved out the shapes of the buildings and the colors changed to pinks and blues. On his many bus rides to places along the East Coast, Lovecraft must have seen thousands of sunsets, looking out the window of the rattling bus after the light became too dim to write or read. He saw New York City for the first time in the light of a sunset. There is that moment sometimes when the orange light seems to inflame the whole world, when Sunset’s Gate seems about to open and you could step through to whatever waits beyond. There’s an old anime and manga cliché dating way back to the ’60s or ’70s, in which characters — usually young, hopeful characters like aspiring soccer champions or something — race across a grassy field towards the sunset, to see who can get there first. In the end, as the sun goes below the horizon still un-caught, they stop and rest, lying in the grass, happy and exhausted, ready to go home and get some dinner and sleep. Or maybe the scene fades out with them still chasing their dream. To continue Wilson’s evolutionary hypothesis, perhaps sunset triggers an instinctive urge in diurnal creatures to return home, to seek shelter and sleep. On the most crass level, heartwarming images of houses seen by sunset are just part of the human emotional spectrum, packed and sold in motivational calendars and Thomas Kinkade paintings and other pop culture trash.

“How often we have seen that City of Never!” wrote Lord Dunsany. “Not when it is night in the World, and we can see no further than the stars; not when the sun is shining where we dwell, dazzling our eyes; but when the sun has set on some stormy days, all at once repentant at evening, and those glittering cliffs reveal themselves which we almost take to be clouds, and it is twilight with us as it is for ever with them, then on their gleaming summits we see those golden domes that overpeer the edges of the World and seem to dance with dignity and calm in that gentle light of evening that is Wonder’s native haunt. Then does the City of Never, unvisited and afar, look long at her sister the World.”

In Dream-Quest, the ultimate unattainable city turns out to be the glorified image of the narrator’s hometown, “moulded, crystallized and polished by years of memory and of dreaming.” When I first read Dream-Quest at the age of 13 or so, I found the ending kind of a letdown, because I didn’t want the Sunset City to be Boston. I wanted less realism; I wanted MORE alienage, MORE wonder, MORE exotic fantasy. But eventually, I grew to appreciate the poignancy of this message, and its appreciation that memories and observed realities are important, that past experiences are the building material of great things. Still, it leaves me wanting more: surely, when we seek the Unknown, we’re not always just wanting to be home again, with a candle at the window, a warm supper, a familiar face? I don’t think that all travels return to the same place; I do think it’s possible to end up somewhere (or someone) different, not just to go back to Square One saying “There’s no place like home” or “It was just a dream.”

But that would be a different story. Maybe Lovecraft could have carried a piece of Providence with him anywhere, even had his physical body lived in Chicago, or Florida, or New York. Luckily for us, he did leave a piece of his ideal city behind; in his writing. And today, armchair adventurers can still look back on these fabulous places retreating ever farther back in time, on old-time Providence, and Quebec, and Arkham, and Kadath.

This is a piece I did back in 2008. I used a selection from it as the sidebar of the mockman.com blog from 2009-2011, but Jay convinced me that it was too jarring an image to show up on the top page all the time. I intended this piece (a gift to a friend) to send an encouraging message of cooperation — the two birds working together to defeat the snakes — but really, it isn’t encouraging at all. The primary mood is of anger and conflict — the sternly judging eyes of the birds, the violence of the flames and ice and the squirming animals.

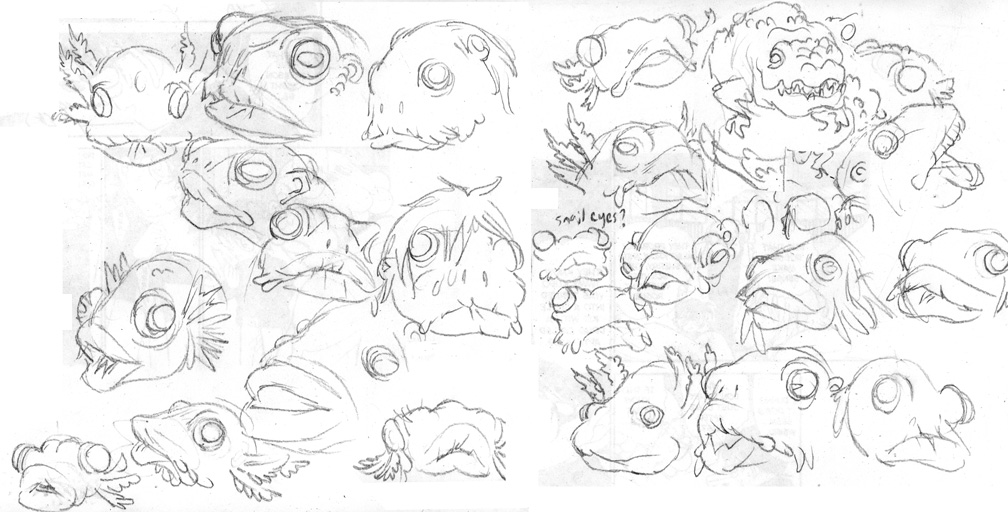

For the poster map of the Dreamlands, I wanted to get away from the standard design of the “Dreamlands map” printed in various Call of Cthulhu Dreamlands supplements (beautiful though it is). My B&W map included in the book, for all my efforts to make it different, is inevitably influenced by the Call of Cthulhu design that I pored over so many times from the time in high school when I bought H.P. Lovecraft’s Dreamlands.

My first thought in drawing the new map was, I wanted to show EVERYTHING, including the southern edge of the world which no one ever draws because all the action in “Dream-Quest” is in the northern half. (Kadath seems to be at the north pole, although there are “rumoured abnormalities of proportion in those trackless leagues” of the north, presumably meaning that extremely long distances of space are compressed into the area around it, as shown in the scene when the night-gaunts are drawn towards Kadath at the speed “of a planet in its orbit” and it still takes them awhile to get there. This image may have been inspired by a scene in Lord Dunsany’s “The Queen of Elfland’s Daughter” where the King of Elfland magically pulls Elfland away from the real world to thwart a questing knight, so that the knight would have to walk millions of miles. It also makes me think of Son Goku walking 1,000,000 km on the Serpent Road in “Dragon Ball,” but anyway.) As this sketch shows, I had the idea of drawing the whole world as a globe floating in space, surrounded by other spheres/planets, the celestial gardens watered by the Arinurian Streams, and the oceans of the world spilling out into space in certain places, like a fountain.

In my first draft of the map, I tried to draw all the mountains and cities radiating out from the middle. I had the idea that, if Kadath was the north pole, the Sunset City/Hesperia should be on the south pole, since it fulfills the role of a mirror/shadow of Kadath in “Dream-Quest.” (And after all, Nyarlathotep does tell Carter that the City is somewhere in Earth’s Dreamlands.) Since it’s on the south pole, I placed it behind the Mountains of Madness, which I assume are in the Dreamlands, since the name was invented by Lord Dunsany in his dream story The Hashish Man. However, although I think the radial map was a good idea, in practice it proved to be difficult to draw recognizable landscape features and make it look good from every angle. (Plus it was pointless, if people were going to be keeping the map on their wall and not turning it constantly.) Also, I knew I was designing the map for a 2’x3′ poster, and it looked weird having the world shaped like an oval. Then there was the everpresent problem of drawing the ‘whole world’ in Mollweide projection even though the Dreamlands are clearly supposed to be flat or flat-ish — since you call fall off the edge of the world past the Basalt Pillars of the West, and in the East, if Gary Myers is canon, the world is bounded by Mhor, and the Vale of Night beyond.

After such thoughts, I eventually decided to redraw the whole world in the style of a bi-hemispherical world map, of the type which was popular in the early 18th century. I placed Azathoth on the top of the map, ruling over the world, in the position that Christ sometimes occupied in Medieval mappa mundi. Drawing the world as a bi-hemispherical map, of course, is a bit of an illusion, since this map is obviously flat and continues off the edges, instead of being a true bi-hemispherical map where the top and bottom edge represent the North and South Pole. So the bi-hemispherical effect is just for style. (Unless, perhaps, the Dreamlands are actually flat and shaped like two joined circles?) But I have to agree with the writers at Chaosium that the Dreamlands look better when the edges are indistinct — certainly the world of dreams is as infinite as the human mind, and potentially continues out in all directions. At first I wanted to show everything, but actually it was better not to.

The scale of the map, roughly, is that 1 inch of the printed edition equals 5.5 days of travel by horse or sailing ship. However, this is also clearly modified by the weird geometry and local spatial irregularities of the Dreamlands. Like Kadath in the north (offscreen in the final map), Mhor in the east is clearly waaaaaaay far away from everything else, years away: in “Xiurhn” Gary Myers writes “That even the East must end if one only travels far enough, all sane men know… but Thish on his journey watched the four seasons of the Earth come in file down through the fields of man and the fields that know him not, come each and pass and come again.” But I wanted to draw it, so I included it on the map anyway. Who knows what is the boundary of the western and southern edges of the Dreamlands?

I tried to resist inventing my own place-names (though there are some) and to instead go for Alan Moore style info-otaku mania. If you dig around you should be able to find 98% of the place-names on this map in the works of Lovecraft, Dunsany or other authors. Lastly, I handled the “Does ‘The Doom That Came to Sarnath’ take place in the Dreamlands, or the distant past?” debate by deciding that the answer is: both. Perhaps ancient places live on in the Dreamlands, and the boundaries of the Past and the Imaginary become blurred. Thus, real places like Khem (Egypt), Meroe, Chaldaea and Ophir, which Lovecraft thought were exotic, are part of the Dreamlands. This explains how the Wanderers in The Cats of Ulthar are clearly supposed to be Ancient Egyptians, even though it’s a Dreamlands story. (Although in “The Loot of Golthoth” Gary Myers came up with the idea that they’re actually from the city of Golthoth, the Dreamlands analogue of Egypt… but maybe Egypt was founded by people who fled Golthoth? Or vice versa?) Returning to the roleplaying game, the Chaosium explanation for the Dreamlands’ ancient technology (why you can’t bring guns there, basically) is that only things that are 500+ years old can exist in the Dreamlands, because it takes that long for things to “set” in the mold of the human collective memory. Perhaps another answer is that these ancient cities and civilizations, like Mesopotamia and Egypt, exist in the Dreamlands because it was here that humans developed consciousness, and these First Cities are and will always be permanently burned into the human brain, but in the year 2500 the Dreamlands won’t be full of Starbuckses. I’m not designing a RPG here, so I don’t really care if some rules lawyer runs around the Dreamlands with a tommygun. It could be entertainingly absurd, really, kind of like later-period ironic Lord Dunsany as opposed to early-period serious Lord Dunsany. Oh, that’s right! Lord Dunsany! I’m going to write about him in my next post.

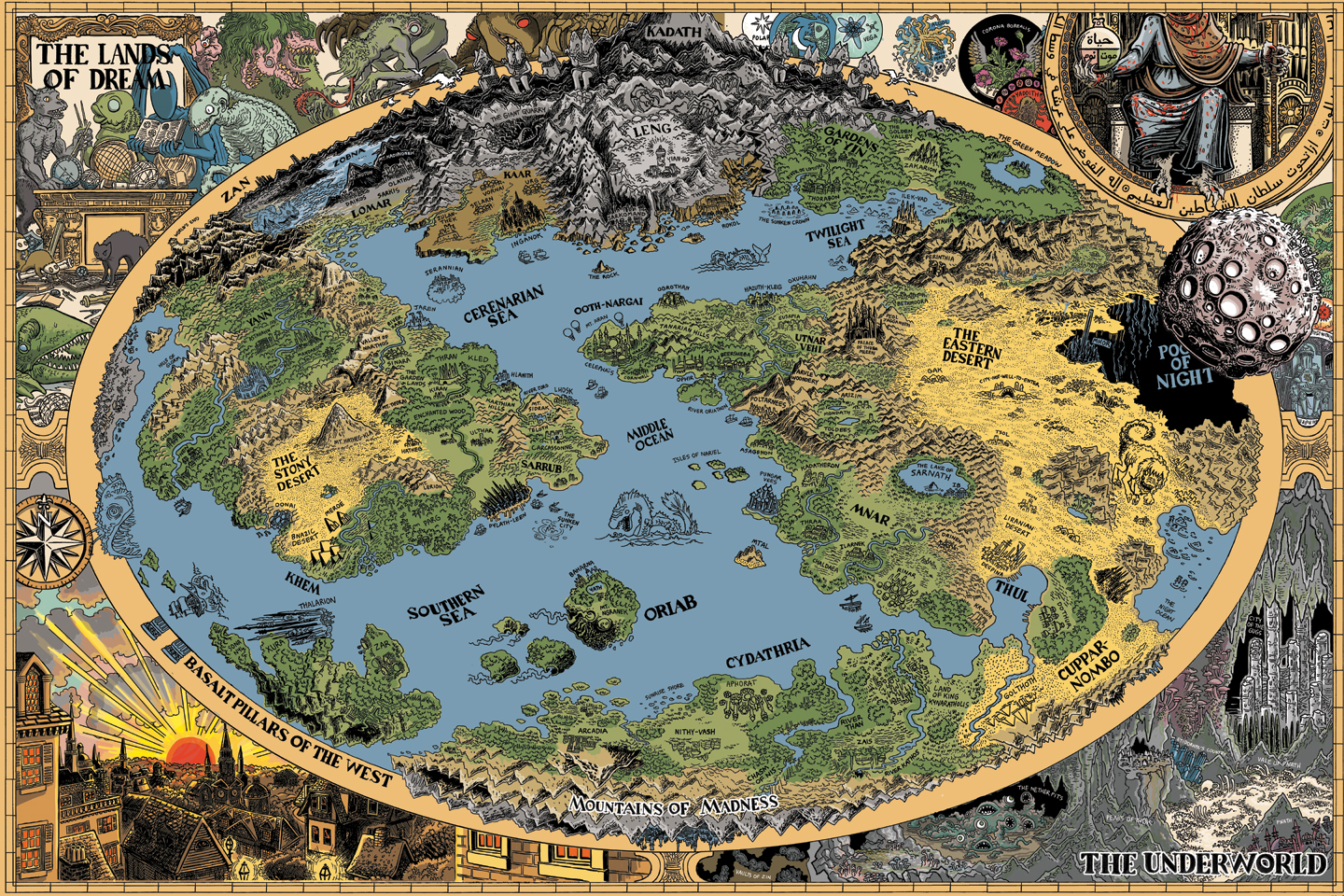

What inspired H.P. Lovecraft’s Dreamlands stories? You could list his childhood fascination with the Arabian Nights; his adult fascination with neo-Arabian fantasies like William Beckford’s Vathek; the pulp fiction of Edgar Rice Burroughs; or even the occasional fantasy stories of Edgar Allen Poe, such as his 1844 poem Dream-Land. But by Lovecraft’s own admission, the author who influenced him the most — not just in the Dreamlands but even his later works, like “At the Mountains of Madness” where the Antarctic vistas are constantly described as “Dunsanian” — was Lord Dunsany, aka Edward Plunkett, 18th Baron of Dunsany.

I got thinking about Dunsany when I found a copy of “King of Dreams,” a memoir of Dunsany in his later years by Hazel Littlefield. Unfortunately, this book was boring and basically seemed like Littlefield trying to cash in on her correspondence with Dunsany, but it led me to Mark Amory’s much-superior biography of Dunsany, which I found in the library while looking for ST Joshi’s out-of-print and expensive “Lord Dunsany: Master of the Anglo-Irish Imagination.” As Joshi and T.E.D. Klein pointed out, Dunsany, an aristocrat from an extremely old and wealthy family, lived the sort of life that Lovecraft might have dreamed of living. Born in 1878 in England, he was raised between England and the green hills of his family lands in Ireland, in a castle that looks like this. His immediate family was not large; he had only one brother, with whom he did not get along. He became happily married in his twenties, and they had one son, who in turn had one son, the painter Edward Plunkett. Mark Amory’s biography of Dunsany was written with the cooperation of the family, since Amory was a college friend of Edward’s, and as a result it doesn’t have all the dirt and speculations that biographies of Lovecraft do. But it has lots of interesting details, and it tells the story of how Dunsany went from having to pay for the publication of his first book, “The Gods of Pegana”, to becoming one of the most acclaimed authors in the English-speaking world by the early 1920s.

Like most Lovecraft fans, I discovered Dunsany through Lovecraft, but I wasn’t quite prepared for what I found. Dunsany’s work isn’t as horror-focused as Lovecraft, and his pseudo-Biblical writing style and often allegorical tales of Gods, Time and Death were a different level of fantasy from Lovecraft’s dream-stories, which even at their most ornate, are always basically about some material real-world thing like a war with frog-people or cats eating someone. As I dug deeper, past Dunsany’s more aery and philosophical work in his early collections “The Gods of Pegana” and “Time and the Gods,” I discovered that Dunsany actually could write some real horror stories when he wanted to, as well as more visceral fantasy stories of monsters and dragons and adventurers. But even in his most down-to-earth stories, Dunsany had a knack for evoking a feeling of weirdness, of wry humor, of exotic solemnity like you’re reading a story found on an ancient papyrus or a buried clay tablet. (He even self-parodied this style, in later stories like “Why the Milkman Shudders When He Perceives the Dawn.”) Most modern writers of fantasy write about elves and wizards with flat realism and scientific exactitude, but Dunsany was writing invented mythology, creating worlds and gods and names out of nothing, then throwing them back into nothing again.

Of course, they weren’t really out of nothing. Dunsany was inspired by Greek mythology, as well as by the Bible, which he appreciated not as religion but as literature. (Amory recounts an apocryphal tale of 19th-century Irish atheism: “George Moore had been a middle-aged man when he broke in on Lord Howard de Walden crying ‘Howard, Howard, I’ve found the most wonderful book. Have you ever read THE BIBLE???'”) Dunsany’s early fiction was also very much in the style of 19th century Orientalism, sating a Western appetite for tales of the exotic lands of the East, of which Bible Lands were a part. What Dunsany was smart enough to realize is that these stories don’t really need to be based on any facts, so instead of setting his tales in China like Ernest Bramah’s Kai Lung stories, or more recently, Barry Hughart’s stories of Master Li and Number Ten Ox (“tales of an Ancient China that never was”), he preferred to set his tales in completely imaginary lands like Pegana and Arizim and Utnar Vehi. The great-great-grandfather of fantasy literature, William Morris, had written his his bland stories as an intentional recreation of Medieval European tropes: but Dunsany and writers like him gave their readers the experience, not merely of the Old and Heroic, but of the Exotic. For Morris, like Medieval balladeers singing about King Arthur or Greek bards writing about the Trojan War, the past was THEIR Past, a sort of nationalistic time of glory when giants walked the earth. (Yawn.) For Dunsany, who knew a bit more about science and archaeology, the past was the Other, a strange, dim world of once-glorious alien cultures now reduced to a few broken idols (“Chu-bu and Sheemish”, “The Men of Zarnith”) or bits of rubble (“In Zaccarath”). Dunsany wasn’t explicitly racist like Lovecraft (perhaps because he was rich; Lovecraft’s racism seems inextricably linked with his poverty and his fears of dispossession, of losing his imagined racial inheritance), but like many period authors, he blurred the Past and the East; in Dunsany, as you travel farther away from London, farther into the East’s opulence and cruelty, it’s like traveling back in time.

In my opinion, Dunsany’s best work is the short story collections “A Dreamer’s Tales,” “The Book of Wonder” and “The Sword of Welleran”, and the novel “The King of Elfland’s Daughter” (his favorite of his own books, and the only one to be adapted into an electric folk rock album narrated by Christopher Lee). But others might disagree; Mark Amory felt that his later, more realistic novels, such as “The Curse of the Wise Woman,” were his best works, and the only Dunsany film so far, Alan Sharp’s excellent but slow-moving 2008 film “Dean Spanley,” is based loosely on one of his later works. (On the other hand, Neil Gaiman’s “Stardust” is sort of a tribute to early-period Dunsany and “Elfland” in particular.) Dunsany went through many different phases, from his early short stories of pure mythological fantasy to his later novels set mostly in Ireland. (Perhaps it’s not merely a coincidence that, after Dunsany traveled to Africa and the Middle East in his 30s and 40s, the “Oriental” element in his fiction faded rather than increasing.) Lovecraft preferred his earlier work, for obvious reasons. Dunsany’s early work is serious, earnest fantasy — it never takes us out of the dream state — but as time goes on he develops a taste for sarcastic authorial intrusions and obvious nonsense, such as stories that go nowhere or tease us with a reveal that never comes. Even the names become sillier: Zaccarath, Allathurion and Perdondaris change to Tong Tong Tarrup, Plash-Goo and Neepy Shang. Basically, his dream stories become parodies of themselves: look at the difference between “Idle Days on the Yann” and its two sequel stories, “A Shop in Go-By Street” and “The Avenger of Perdondaris.” Eventually, Dunsany moved on to a new phase and stopped writing ‘dream’ stories altogether. From that point onward, he would write chiefly about the Irish countryside, and how great dogs were, and Jorkens, a British raconteur who drank whisky and told tall tales.

Dunsany was a political conservative, and even in his lifetime he was criticized for being against women’s suffrage, Irish independence, etc. He also had little taste for modern literature or poetry; he never read “Ulysses” and, according to Hazel Littlefield, he spent a lot of time in his later years complaining about free verse and Dylan Thomas and other modern foolishness. Dunsany’s work romanticizes preindustrial society, childhood memories (“The Long Porter’s Tale”) and occasionally the homeland (“The Sword of Welleran”); for these reasons Michael Moorcock really rips him apart in his famous essay Epic Pooh, claiming that he’s conservative and boring, an example of the bad kind of fantasy: the “prose of the nursery-room.” But, like C.S. Lewis, who once wrote “Some day you will be old enough to start reading fairy tales again,” I don’t think Dunsany would have ever denied that his tales are basically children’s stories for adults. And while Dunsany’s work wasn’t leftist by any means, and he wasn’t really interested in assaulting taboos (in later life he was offended by the beat poets’ treatment of religious subjects), his many parables on nature show an incipient environmentalism, and his work has a clearly atheistic message on the whole. His early play The Glittering Gate offended at least one contemporary reviewer; in this almost Samuel Beckett-like short piece, two thieves wait outside the Gate of Heaven trying to get inside, only to discover at the end that Heaven doesn’t exist.

Dunsany also has a taste for horror. He wrote a few actual horror stories — such as “The Exiles Club” — but even in his dreamier fantasies Dunsany, a lifelong prankster and sayer of outrageous things, delighted in the kind of shocking asides designed to upset polite conversation in drawing rooms. In “The Chronicles of Rodriguez” the bell-pull at the gate of a wicked palace is connected to a hook in the guts of a prisoner, which when pulls, causes the man to scream. In “The Hashish Man” we see a sailor being tortured: “They had torn long strips from him, but had not detached them, and they were torturing the ends of them far away from the sailor.” Throughout his work there are Unspeakable Fates and Unnameable Things aplenty (from “The Probable Adventure of the Three Literary Men”: “Something so huge that it seemed unfair to man that it should move so softly stalked splendidly by them, and only so barely did they escape its notice that one word ran and echoed through their three imaginations — “If — if — if.””) Simply put, Dunsany had a flair for creating striking images of wonder and horror in a few words, something Lovecraft wasn’t nearly as good at.

Lovecraft discovered Dunsany in 1919 and basically turned instantly into a crazed fanboy, although he always preferred Dunsany’s early, exotic work to his later dogs-in-Ireland stuff. Lovecraft was fortunate enough to get to see Dunsany face-to-face while Dunsany was on an American book tour, although he didn’t talk to him; in S.T. Joshi’s words, Dunsany was unaware that “the lanky, lantern-jawed gentleman in the front row would become his greatest disciple and a significant force in the preservation of his own work.” While he was alive, Dunsany was a bestselling author and a contemporary and friend of William Butler Yeats and George Bernard Shaw; but after his death, his literary star faded faster, and much of his early work was out of print until Lin Carter reprinted it — with a glowing quote from Lovecraft on the back cover — in his 1970 Ballantine Fantasy series. I sometimes wonder how the Dunsany estate feels that so much attention to Dunsany today comes by way of Lovecraft, who wasn’t 1/100th as popular as Dunsany during their shared lifetimes; someone — I think it was Darrell Schweitzer — told me at one of the NecronomiCONs that the agent in charge of the Dunsany literary estate in the ’90s hadn’t even heard of Lovecraft until Schweitzer told them about him. (I’m sure they’ve heard of him by now, though.) Interestingly, Dunsany actually lived long enough to read Lovecraft’s fiction; he was introduced to it by Arthur C. Clarke, and there’s references to it in Clarke and Dunsany’s correspondence. Unfortunately, I don’t own this rare, out-of-print collection, so all I remember from an old review of it is that Dunsany said “I see this Lovecraft fellow borrowed my style… (but) I don’t begrudge him it….”

Perhaps one of the reasons Dunsany isn’t as popular today as Lovecraft or Howard is that he never created a coherent mythology from one story to another. (The closest is “The Gods of Pegana,” which is almost like a novel or a faux religious text, since all the stories involve the same gods.) Lovecraft and his contemporary writers in Weird Tales were enthralled with the idea of creating consistent worlds with connections from one story to another, whether out of personal obsessive-compulsiveness (in Lovecraft’s case) or perhaps the desire to create a franchise universe, like the worlds of Edgar Rice Burroughs and L.Frank Baum. Dunsany never did this; each of his stories is its own separate world. At best there’s a few tiny threads the completist can pick out: “Idle Days on the Yann” has its sequels, and some of the same place-names reappear in “Bethmoora”, “The Probable Adventures of the Three Literary Men” and “The Hashish Man,” in which we hear that the emperor Thuba Mleen has a curtain “engraved with all the names of God in Yannish.” So is Yann not just the name of a river but of a language? “The Hashish Man” also involves the idea, borrowed by Lovecraft in “Celephais,” that these fantastical realms exist somewhere outside human perception, and one can visit them via dreams or drugs — or is the person who talks to the narrator of “The Hashish Man” claiming to have dreamed of Bethmoora merely a madman? In any case, it’s one of Dunsany’s best stories, and a major influence on the development of the Dreamlands. (According to Amory, Aleister Crowley also liked “The Hashish Man.” Crowley sent Dunsany a fan letter, teasing him with “I see you only know hashish by hearsay, not by experience… You have not confused time and space as the true eater does” and also including a gift of some “erotic magazines.” Dunsany was apparently amused and, in a typical display of reserved humor, sent Crowley a thank-you note saying the strongest drug he took was tea.)

I think one of the differences between Dunsany and Lovecraft’s writing is simply that writing came easier to Dunsany than to Lovecraft. Dunsany could write an entire play between lunch and dinner; Lovecraft re-wrote and re-wrote and re-wrote. Dunsany’s early literary career was a stellar rise, and Dunsany knew it — he often referred to himself as a “genius” — whereas Lovecraft’s career was marked with depression, self-deprecation, rejection, poverty. Dunsany traveled around the world, was a guest of Indian Maharajahs, briefly tried his luck as a politician, fought in two wars (the Boer War and WWI), narrowly avoided being bombed in a refugee freighter in the Mediterranean in WWII, and was shot in the face (it was just a flesh wound) during Protestant-Catholic conflicts in Ireland. In contrast, Lovecraft did almost nothing, and yet Lovecraft’s writing seems more personal than Dunsany’s, one gets more of a sense of his personality and the neuroses that underpinned his brief life. Yet even if Dunsany doesn’t bare his own hopes and fears in his fiction as much as Lovecraft does (Alan Sharp had to pretty much make up all the emotional hooks and characters himself to turn “Dean Spanley” into a movie), his work still has emotion — “Where the Tides Ebb and Flow” is one of the saddest stories imaginable, “Poltarness: Beholder of Ocean” is a close runner-up, and “The King of Elfland’s Daughter” is an epic love story. Without Dunsany’s work — his flair for language, his love of the exotic, his invented Gods, his obsession with time and the transience of humanity — HP Lovecraft’s fiction might have turned out very differently. He enriched the fantasy world with his stories of Bethmoora and Gnoles and Gibbelins, and at his best, his writing shines in a way Lovecraft’s never did.

Here’s some more sketches of what ended up becoming the Map of the Dreamlands. A “globe floating in space” design could have been interesting, but it would also leave too much empty space around the world for my taste. The fact that most of my sketches and designs are drawn on scrap paper and the backs of envelopes is one reason I don’t post more of ’em… should I show ’em anyway?

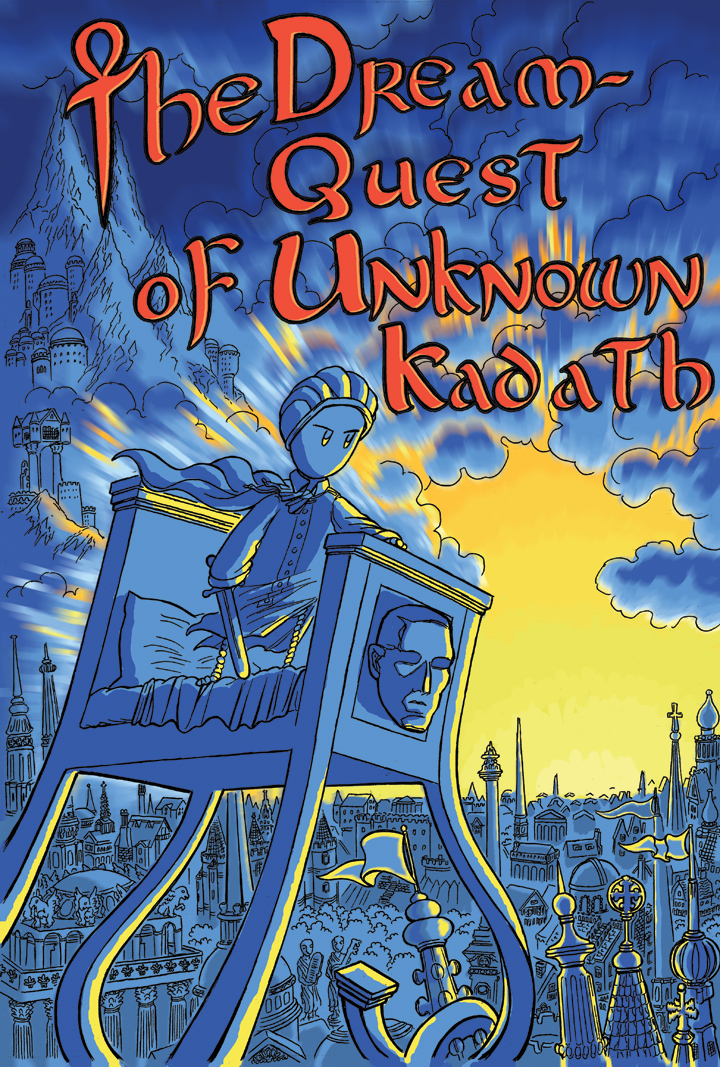

I’ve been planning to do a Dream-Quest graphic novel for some time, and I did a few different cover treatments before coming up with the final version.

The original cover for issue #1 of the comic series, which I drew waaaay back in 1997, wasn’t great, but it was one of the better covers of the original five-issue series because I was smart enough to use a limited color palette. Color was still not my thing, though. I tried to duplicate the same “sunset sky” (although doesn’t it look more like dawn?) limited color palette, with better lineart, for the first version of the cover:

But, as time passed I decided I didn’t like this design anymore. It was too simple, the Photoshoppy colors needed work, and the massive, cover-dominating logo looked bad. In 2011, when the Kickstarter got going, I decided I wanted to do a wrap-around cover instead!

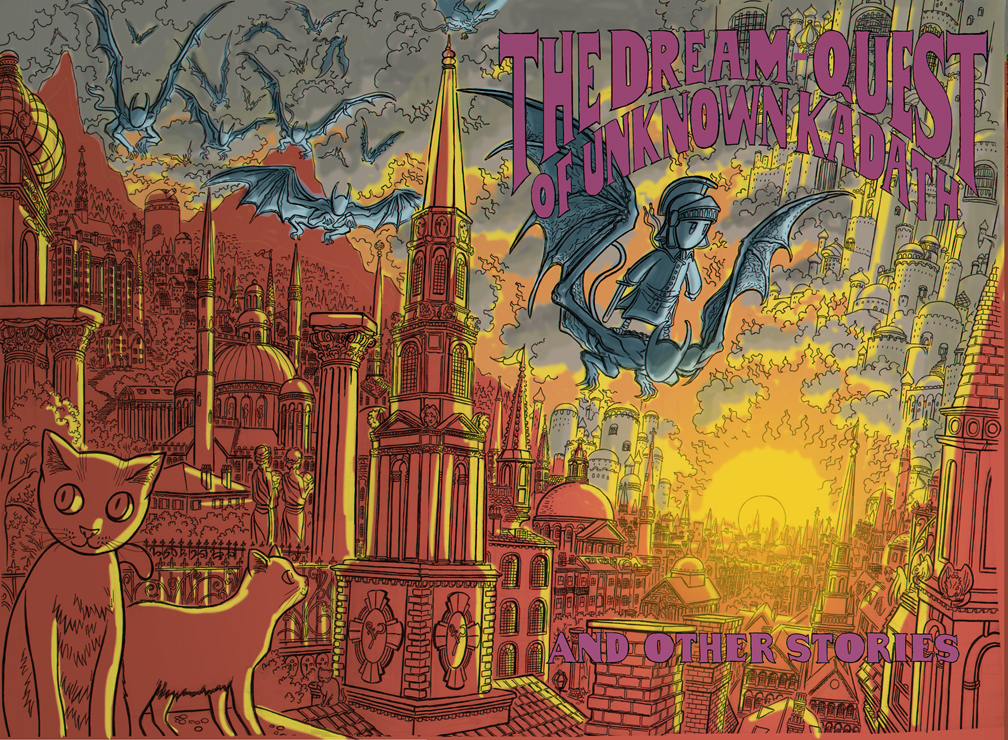

Aside from the sunset city, there were two other images that screamed “Dream-Quest” to me: the actual castle of Kadath (but that’s kind of a spoiler) and the scene when the black galley goes off the edge of the world. The black galley scene was used as the cover of Edward Martin III’s Dream-Quest movie, after all. I considered an epic shot of galleys plunging off the edge of the world into space, crewed by — cats? Randolph Carter? Evil merchants? Ghouls? Possibly Basil Elton, Kuranes and the other dream-story protagonists?

A sailing ship with all its sails and ropes would have been a great image for the front cover, and would have really given off a feeling of adventure. But in the end I decided that a bunch of ships crewed with different Lovecraft characters would suggest that the graphic novel was some kind of Lovecraft mash-up instead of an anthology, and I went with the sunset city, for a more whimsical, children’s-booky look. (With the addition of a nightgaunt steed to replace the Little-Nemo-in-Slumberland walking bed of the original comics front cover.) My first draft had a fiery, apocalyptic Photoshopped look — “through sunset’s gate He swept me, past the lapping lakes of flame, And red-gold thrones of gods without a name” — but eventually, I decided on more natural, subdued colors. The actual final color covers were done entirely by Jay, who spent hours and hours on the Cintiq working with her brush pen. All the intricate, loving detail on all the grassy cobbles and red roofs are all hers. Although I love black and white, I hope to do more color work of my own someday soon…