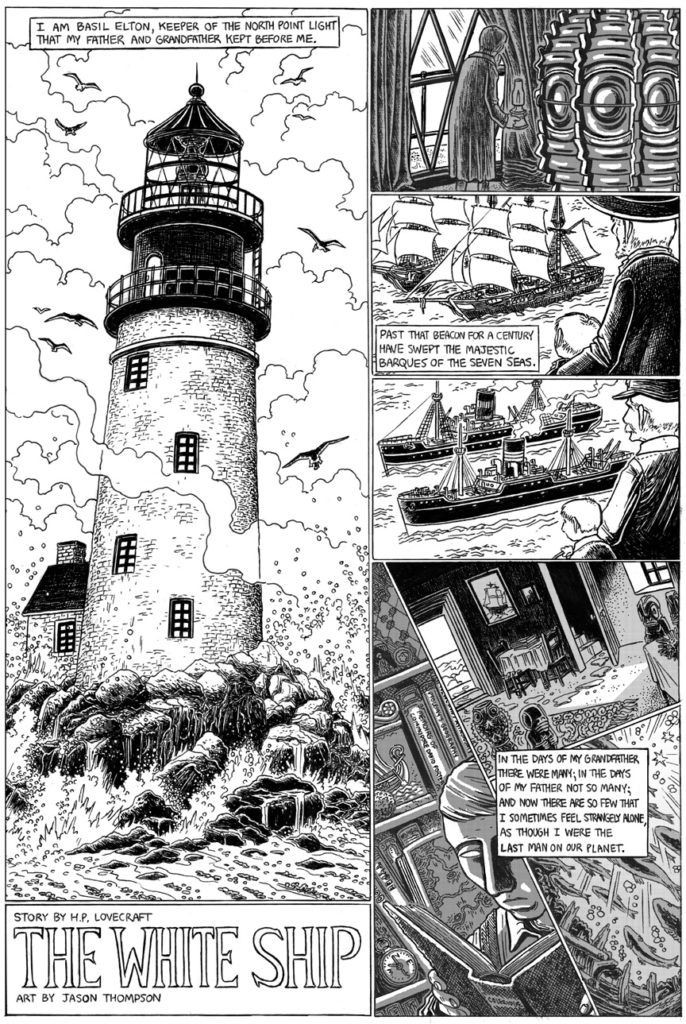

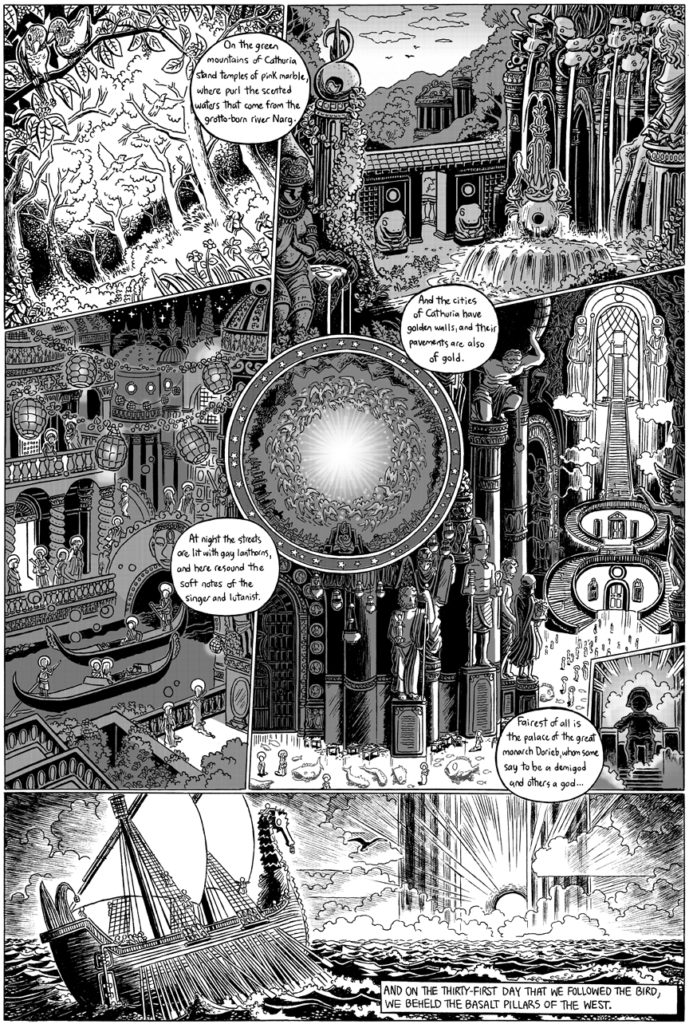

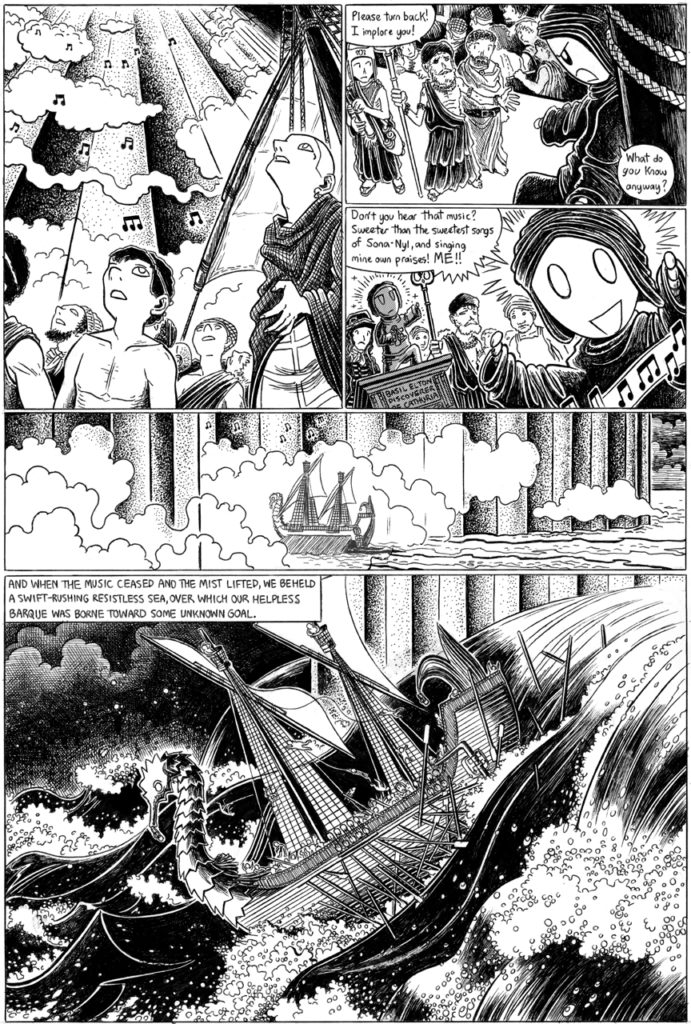

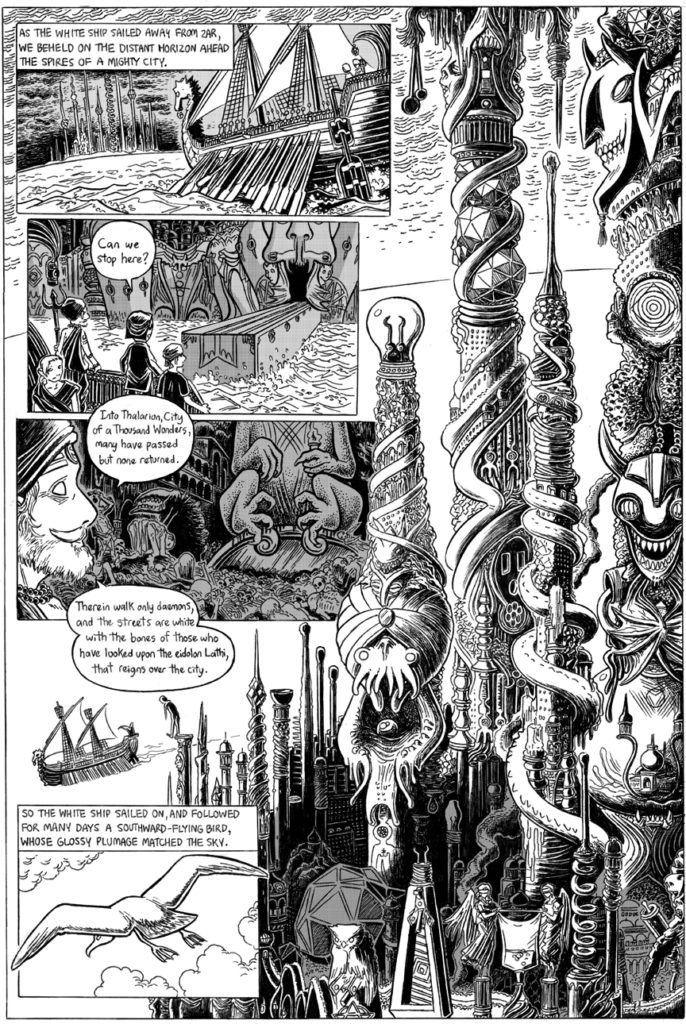

I gave the original of this page to my good friends Shaenon Garrity and Andrew Farago. Incidentally, I wouldn’t have drawn fantasy comics if not for Alberto Manguel and Gianni Guadalupi’s Dictionary of Imaginary Places, which, although it gives Lovecraft’s stories relatively short shrift, is an unbelievable book filled with fascinating details and inspiration.

On another note, I finally watched Lovecraft: Fear of the Unknown, 2009’s long-awaited first real documentary about H.P. Lovecraft. Aimed at the Lovecraft newbie, the documentary spans his birth to his death and his posthumous rise to fame. From Lovecraft’s father’s descent into insanity and institutionalization, to his home life alone with his also unstable mother supported by their dwindling inheritance; from his time as a high school dropout and his deep depression to the friendships he made through “amateur journalism” (a term the filmmakers could have defined better); from his marriage and move to New York, to his divorce and return to Providence, Rhode Island; this documentary gives us an outline of Lovecraft as a human being. It’s also an introduction to his work, however, full of images of grotesque monsters and dark crypts, and much discussion of the elements that make Lovecraft so enduringly popular. It’s a lot to squeeze into 90 minutes.

The documentary is obviously low-budget. The camera pans over a lot of clip art, including lots of artwork by Lovecraft-influenced artists, some of it really good; on the other hand, the profusion of different styles throughout the film is a little distracting, and I wish they’d had the budget to hire one single solid artist, maybe Tom Sullivan or John Coulthart, to provide running illustrations of the stories in a consistent style. (More period illustrations might also have helped sustain a mood.) Moving images, beyond the talking heads of the interviewees, are sadly almost absent. Certainly for financial reasons, there’s nary a clip from the many Lovecraft-influenced films, including the ones by interviewees John Carpenter and Stuart Gordon (of course, almost all Lovecraft films are awful, so that may be another reason they’re not included). Still, a few old 1920s-era film clips of street scenes and the like, and perhaps some public-domain music from the same time period, would have done a lot to bring Lovecraft’s contemporary world to life. It would also have been nice to include some modern-day walking shots of New York, Providence and Marblehead, letting us explore the places where Lovecraft lived and which inspired him (another totally subjective criticism: I wish they’d filmed Providence in the spring or summer when it’s prettier, to quote Lovecraft, “when the alchemy of nature transmutes the sylvan landscape to one vivid and almost homogeneous mass of green; when the senses are well-nigh intoxicated with the surging seas of moist verdure…”). The swirling distortion effects (to liven up the clip art) and Mars’ constant, uneven musical score made me feel at times like I was watching a super-low-budget horror movie, not a documentary.

As might be expected by the box copy that describes Lovecraft as a “xenophobic Old World gentleman,” the documentary tries to soften Lovecraft’s racism. As a brief early example of Lovecraft’s “xenophobia,” the narrator quotes a brief tirade against Russian immigrants from one of Lovecraft’s letters. Of course Lovecraft’s racism *was* based on xenophobia (and classism), but its use here is obviously weasel words; the makers of the documentary are so eager to make Lovecraft look acceptable to modern tastes that they avoid quoting from any of his zillions of much more shocking and racist rants about Jews, Arabs (Lovecraft was an Anti-Semite in the old-fashioned all-inclusive sense), African-Americans, Asians, the healthy joy of Aryans crushing barbarian skulls, etc., as reprinted in Arkham House’s Selected Letters. The narrator glosses over this, so that when they go on to describe the plot of “The Rats in the Walls” and offhandedly mention that the cat in the story is named “Niggerman,” I can see a casual viewer going “WHAT?!?!” A little later, in the section describing Lovecraft’s New York sojourn, they do utter the “racism” word and quote one of his more famous (but still nonspecific) rants about “biologically inferior scum”, but they could have been much more excoriating towards Lovecraft in this regard. Neil Gaiman disses ‘amateur psychologists’ who would say that Lovecraft’s stories are just sublimated racism, and Guillermo del Toro (who nicely deflates things by describing Lovecraft as “someone who probably didn’t get laid very much”) advises us to put everything in historical context. Since apparently some reviewers of the DVD on amazon.com were shocked by what little of his racism they do show, I can’t imagine how much more freaked out people would be if they had spent more time looking into this aspect of his character. But it’s pretty obvious if you read his writings, particularly his earlier stories, like “Herbert West: Reanimator” or the awful “Medusa’s Coil.” To address this more directly would be the sign of a more confident documentary.

(To nitpick a step further, it doesn’t help when Frank Woodward, the maker of the documentary, says in an interview with suvudu that a lot of people he knew became Lovecraft readers after September 11th. This is either a simplistic answer — ooooh, September 11th shocked Americans with the cosmic horror of the blind uncaring meaninglessness of existence — or it says things about the racism in Lovecraft’s fiction that the filmmakers probably didn’t intend to say. I’d prefer to think it’s the former.)

The documentary spends a lot of time describing the plots of Lovecraft’s fiction. Although this is helpful, I wish there was more of Lovecraft’s own words and the words of his contemporaries (such as his wife), and less of the narrator and interviewers describing how Lovecraft probably felt. At times the narrative voice doesn’t feel quite professional; it sounds weird to hear them throwing around flowery Lovecraftian words like “Cyclopean” and “corpse-city” in paraphrased, rather than quoted, descriptions of Lovecraft’s fiction. Similarly, a digression mocking/defending Lovecraft’s hyperbolic use of adjectives feels a bit like “methinks thou dost protest too much”; it’d seem more relevant if the documentary included more long quotations from Lovecraft’s work so we could form our own opinion before they started making excuses. They specifically discuss “Dagon,” “Herbert West, Reanimator,” “The Outsider,” “The Rats in the Walls,” “The Call of Cthulhu,” “The Whisperer in Darkness,” and “At the Mountains of Madness.” (I may have forgotten one or two.) The summaries aren’t bad, but only the summary of “At the Mountains of Madness” really made me feel the thrill of the story, and it’s a rare instance where the musical score helps. With its famous scene in which Lovecraft’s protagonist feels “fellowship and empathy” for the alien life forms, “At the Mountains of Madness” serves as an example of Lovecraft’s evolution from really racist to less racist—although this progression would be a lot clearer if the documentary had dared to show Lovecraft in “really racist” mode.

As with most works on Lovecraft, there is a slight favoritism towards his stories of the Cthulhu Mythos and giant tentacled monsters. It’s not egregious, but the documentary does start with a roll call of the “famous names” Lovecraft created, like Cthulhu, Yog-Sothoth, etc. (No mention of the various hoax versions of the Necronomicon?) Poe and Dunsany are mentioned as influences on Lovecraft, but Lovecraft’s Dunsany phase and “The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath” are ignored. (Not that I’m at all biased in this respect, of course…) After Lovecraft’s death, the documentary briefly talks about his rise to fame, with a nice segment on Arkham House before moving on to a general description of modern Lovecraft-inspired pop culture. “We only parody things that have life. There is no point in making fun of something that doesn’t matter,” Neil Gaiman says.

The interviewees are a good bunch, and provide the best content in the documentary. The witty, opinionated ex-clergyman Robert Price gives it to all sides; Ramsey Campbell and S.T. Joshi are great speakers; and Peter Straub, while obviously a Lovecraft fan like all of them, has some harsh words on HPL’s work ethic and his behavior to his wife during his marriage. The “extended interviews” are arranged by subject matter, not by interviewee, which is a shame, as I’d rather have listened to the full unedited interviews with these folks rather than the few clips we have here. We also aren’t given any real information about who the interviewees are, which is a missed opportunity; while most nerds probably recognize Guillermo del Toro and Neil Gaiman, and of course there’s Wikipedia for the diligent, it’d be worth it to get 30 seconds’ introduction to Ramsey Campbell, S.T. Joshi and Peter Straub. Lovecraft’s various contemporary friends, even Conan creator Robert E. Howard and Psycho creator Robert Bloch, are also just names and photos passing by on the screen.

For people who’ve never read S.T. Joshi’s incredible biography Lovecraft: A Life or L. Sprague deCamp’s more critical and less thorough but also worthwhile Lovecraft: A Biography, this is a decent introduction to Lovecraft. It could have moved a bit faster, it could have been longer and, with a bigger budget, more visually and audially impressive; there is also more that could have been done to make Lovecraft seem like a person, not just the workaholic, perfectionistic creator of a bunch of stories. Rather than having quite so much of modern-day people interpreting Lovecraft, an alternate documentary could have taken us inside his own words, warts and all. Lovecraft left behind thousands of letters, and his own words are almost always more interesting than any Lovecraftophile’s. The outline of his life, from his “quarter-life crisis” to his hikikomori self-seclusion throughout most of his twenties, from his epistolary friendships (perhaps the equivalent of online friendships today—as Stephen King said in his book On Writing, Lovecraft was the sort of person who today “would probably be most alive on some Internet messageboard”) to his gradual opening up, is really the archetypal story of a withdrawn nerd. There are so many interesting tidbits about Lovecraft’s life not mentioned in this documentary: the fact that his mother dressed him as a girl when he was younger; his grandfather leading the young Lovecraft through their darkened house at night to cure him of his fear of the dark; his childhood phase of worshipping the Greek gods; his Puritanical thoughts on sexuality; his love of cats, which he never owned, although he named and petted all the neighborhood strays; his impulsive attempt to join the Army in 1918 (“it will either cure me or kill me”); his crappy but endearing artwork, except for a single sketch of Cthulhu shown in the documentary; his wife’s descriptions of him in her pamphlet The Private Life of H.P. Lovecraft; his desperate attempts to find work in New York City; his horrible, very modern nerdy/unhealthy eating habits (he lived on a diet of chili, spaghetti, canned beans, coffee and sweets); his brief part-time job as a movie ticket-taker; his late-in-life political changes and his statements against then-rising Nazi Germany; and so much more. I understand the need to describe Lovecraft’s works and his context in pop culture, but to paraphrase the title of S.T. Joshi’s biography, I’d rather have a little more about “Lovecraft: A Life” rather than “Lovecraft: A Writer.”

This documentary is long overdue, and a labor of love, but I’m more happy that it exists than I am totally happy about the execution. In some ways, I feel that the equally low-budget 1998 documentary/movie Out of Mind, with its frame story and scenes of Christopher Heyerdahl playing Lovecraft, captures the weirdness and charm of Lovecraft’s life in a subtler and more engrossing fashion. It’s just my nature as a fanboy that I want to present Lovecraft to the world in a certain Jason-Thompson-approved fashion, with his best tie on, emphasizing this over that; as for “Lovecraft: Fear of the Unknown,” I think it’s a good try and I’m happy to see such a strong selection of writers, filmmakers and critics talking about him. It’s a shame that this documentary wasn’t made 20 or 30 years ago, when some of Lovecraft’s friends were still alive—Frank Belknap Long, Robert Bloch, Willis Conover, or going back further August Derleth, Clark Ashton Smith, Sonia Greene—and could have talked about knowing him in person. But time moves on, and Time was perhaps Lovecraft’s greatest obsession, as interviewee Caitlin Kiernan suggests briefly. By now Lovecraft is almost outside of living memory; we have recorded all the firsthand observations, all the letters that were not thrown away (like his letters to and from his wife, or his tantalizingly lost correspondence with a member of the NAACP), all the fragments of stories from his attic. Now we can do nothing but sift through the data and rearrange it in different combinations, in different documentaries and biographies and critical articles. Lovecraft is now part of history, part of the buried strata of time, his own Jazz Age as nostalgic to us as the 18th century was to him.

NEXT UPDATE: Tuesday, February 8!